| "There are other worlds. This one is done with me." | | --Merlin (Nicol Williamson) in John Boorman's Excalibur |

The world gets older, and the magic goes away. That has always been the nature of things.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *I forbid you maidens all

that wear gold in your hair

To travel to Carterhaugh

for young Tam Lin is there

None that go by Carterhaugh

but they leave him a pledge

Either their mantles of green

or else their maidenheads

Janet tied her kirtle green

a bit above her knee

And she's gone to Carterhaugh

as fast as go can she |

| She'd not pulled a double rose,

a rose but only two

When up then came young Tam Lin

says "Lady pull no more"

"And why come you to Carterhaugh

without command from me?"

"I'll come and go" young Janet said

"And ask no leave of thee"

|

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Sandy Denny was 21 years old when she joined Fairport Convention. Her voice of this time if you've never heard it is one to give you shivers, warm and full and rounded, and of unfailing and absolute perfect pitch.

The tale is that first the band auditioned her; then, though they had an album out on Polydor already, she auditioned the band. . . .

I've never heard that debut Fairport album with original singer Judy Dyble, but I will nevertheless say that, no matter how good Dyble may have been, a voice like Denny's couldn't help but expand the possibilities open to Fairport.

As would her conversance with English (and Scottish) traditional music. Before Sandy Denny joined, Fairport were a bunch of Brits who wanted to be The Byrds; after she joined, Fairport were the band that others, Steeleye Span and the rest, wanted to be.

It is impossible these days to introduce the term "British folk-rock" into the conversation without mentioning Fairport; they were its first and foremost practitioners, and without slighting the talent that is Richard Thompson's, they were that primarily because of Sandy Denny.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Janet tied her kirtle green

a bit above her knee

And she's gone to her father

as fast as go can she

Well up then spoke her father clear

and he spoke meek and mild

"Oh and alas Janet" he said

"I think you go with child" | "Well if that be so" Janet said

"Myself shall bear the blame

There's not a knight in all your hall

shall get the baby's name

For if my love were an earthly knight

as he is an elfin grey

I'd not change my own true love

for any knight you have" |

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The first written reference to the Scottish ballad commonly known as "Tam Lin" dates from 1549, but there is every reason to suppose that the ballad is in fact much older. "Thomas the Rhymer," a ballad with which "Tam Lin" is often associated, and which shares some thematic similarities with "Tam Lin," originated at least 100 years earlier, and it's also possible that "Tam Lin" is the older of the two.

However old the ballad might be, whoever its original composers and contributors and singers might have been, there's no doubt that that they were practicing Christians. William when he came to do his Conquering came to a thoroughly Christianized land; the last pagan king in Britain had been slain some 350 years before his invasion.

But we all know Christian is isn't always as Christian does. Much of the pagan myth and ritual of the British Isles was not discarded, but was rather subsumed into folklore.

Into folklore like the ballad "Tam Lin," that is. What's interesting to me here is not just that "Tam Lin" is a fairy story with direct links to Celtic belief, but also that the story serves as an allegory as to how that Celtic belief, that Celtic magic if you will, came to be diminished with the spread of Christianity. Unlike many of the folk ballads, "Tam Lin" is understood to have something of a happy ending, but of course it's a happy ending for Tam Lin, and not so much of one for the fairies and their queen.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *So Janet tied her kirtle green

a bit above her knee

And she's gone to Carterhaugh

as fast as go can she.

"Oh tell to me Tam Lin" she said

"Why came you here to dwell?"

"The Queen of Fairies caught me

when from my horse I fell

And at the end of seven years

she pays a tithe to hell

I so fair and full of flesh

and fear'ed be myself

|

| But tonight is Halloween

and the fairy folk ride,

Those that would their true love win

at mile's cross they must hide

First let pass the horses black

and then let pass the brown

Quickly run to the white steed

and pull the rider down,

For I'll ride on the white steed,

the nearest to the town

For I was an earthly knight,

they give me that renown

|

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Fairport Convention released three albums with Sandy Denny in 1969.

What We Did on Our Holidays was followed by

Unhalfbricking was followed by the singular masterpiece of British folk-rock that is

Liege & Lief.

It was like good morning, good afternoon, and goodnight: for after they--she--had revolutionized electric folk, when they were done with these records, Denny made the first of the several poor career decisions that she would make during her lifetime: she quit Fairport.

In hindsight, we can say that neither party would ever be so important or influential again. This may not have been apparent in the immediate aftermath of the split, however: Denny won

Melody Maker's poll as Best Female Vocalist in both 1970 (as a member of her one- or two-off band Fotheringay) and 1971 (when she was promoting her first solo album,

The North Star Grassman and the Ravens).

It became readily apparent, however, as time passed, as Denny's heavy drinking took a toll on her personally, and as her heavy smoking took its tithe on her voice. By 1975, when she had rejoined Fairport for a brief reunion, it was apparent that the bell-like clarity of her voice was likely gone, not to return.

Then, after a final, ill-conceived "contemporary rock" album, one day in 1978 she tumbled down some stairs, perhaps drunkenly, and four days later her voice in whatever form it might have taken was silent.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Oh they will turn me in your arms

to a newt or a snake

But hold me tight and fear not,

I am your baby's father

And they will turn me in your arms

into a lion bold

But hold me tight and fear not

and you will love your child, |

| And they will turn me in your arms

into a naked knight

But cloak me in your mantle

and keep me out of sight"

In the middle of the night

she heard the bridle ring

She heeded what he did say

and young Tam Lin did win |

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Although it's not mentioned in the Fairport rendition, most versions of "Tam Lin" explain that Janet was the heir to Carterhaugh Woods. When the fairies--or Tam Lin as their emissary--forbid her to enter the woods that in fact belong to her, they're not necessarily fighting words, but only because mortals had traditionally not dared to defy the powerful fey in the matter.

As someone who knows a lot more than me on the subject has written: "The battle over Tam Lin is also a battle over the magic in the woods, and whose claim was greater."

The fairies' defeat in the matter of Tam Lin, then, seems to mirror the eclipse of Celtic paganism and its sequestering under Christian envangelism. "Tam Lin," so often noted in this day and age for its strong feminine hero, is pretty plainly to me an allegory for the rise of Christianity, and of course its contrapositive, the death of magic.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Then up spoke the Fairy Queen,

an angry Queen was she

"Woe betide her ill-farred face,

an ill death may she die | | Had I known Tam Lin" she said

"This night I did see

I'd have looked him in the eyes

and turned him to a tree" |

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Sandy Denny's voice at her height, on "Tam Lin," young and powerful, five, six, seven years before things would dissipate messily, is like furniture of fine burnished wood. You can almost smell the lemon oil, watch the rag infused with its essence as it slides frictionless across that polished table top.

Her voice is like Armagnac, caramel, honey, syrup, and the rich rich burn as it envelopes you. It's like violins, layers upon layers of warmth, so deep and so sad you're not sure just how far down it all goes, the vibrato there stately weeping for all the magic yet to be lost.

File Under: British Folk Rock, Scottish Balladry, Songs with versions by Robert Burns

Beyond the tirades of profane baseball men and the clever movie dialogue, there is at least one more great class of spoken word often loaded onto Junior Jr., and that is those endlessly entertaining excerpts from the BBC One radio shows of the late great John Peel.

Beyond the tirades of profane baseball men and the clever movie dialogue, there is at least one more great class of spoken word often loaded onto Junior Jr., and that is those endlessly entertaining excerpts from the BBC One radio shows of the late great John Peel. And we all know that guy who listens *only* to skacore, or to drone metal, or to reggae . . . .

And we all know that guy who listens *only* to skacore, or to drone metal, or to reggae . . . . The other, funnier, thing about Peel after the shining example he set is that he was frequently a klutz on air, banging the desk, knocking over the mike, popping the wrong cart in at the wrong time, forgetting the name of that band's album. But it all emanated from his guileless enthusiasm, and was so therefore wonderful . . . and wonderfully hilarious.

The other, funnier, thing about Peel after the shining example he set is that he was frequently a klutz on air, banging the desk, knocking over the mike, popping the wrong cart in at the wrong time, forgetting the name of that band's album. But it all emanated from his guileless enthusiasm, and was so therefore wonderful . . . and wonderfully hilarious.

But seriously, folks. . . .

But seriously, folks. . . .

Unless I can track down a copy of Soundhog's Mashup album, that is.

Unless I can track down a copy of Soundhog's Mashup album, that is.

I've never heard that debut Fairport album with original singer Judy Dyble, but I will nevertheless say that, no matter how good Dyble may have been, a voice like Denny's couldn't help but expand the possibilities open to Fairport.

I've never heard that debut Fairport album with original singer Judy Dyble, but I will nevertheless say that, no matter how good Dyble may have been, a voice like Denny's couldn't help but expand the possibilities open to Fairport. The first written reference to the Scottish ballad commonly known as "Tam Lin" dates from 1549, but there is every reason to suppose that the ballad is in fact much older. "Thomas the Rhymer," a ballad with which "Tam Lin" is often associated, and which shares some thematic similarities with "Tam Lin," originated at least 100 years earlier, and it's also possible that "Tam Lin" is the older of the two.

The first written reference to the Scottish ballad commonly known as "Tam Lin" dates from 1549, but there is every reason to suppose that the ballad is in fact much older. "Thomas the Rhymer," a ballad with which "Tam Lin" is often associated, and which shares some thematic similarities with "Tam Lin," originated at least 100 years earlier, and it's also possible that "Tam Lin" is the older of the two. In hindsight, we can say that neither party would ever be so important or influential again. This may not have been apparent in the immediate aftermath of the split, however: Denny won Melody Maker's poll as Best Female Vocalist in both 1970 (as a member of her one- or two-off band Fotheringay) and 1971 (when she was promoting her first solo album, The North Star Grassman and the Ravens).

In hindsight, we can say that neither party would ever be so important or influential again. This may not have been apparent in the immediate aftermath of the split, however: Denny won Melody Maker's poll as Best Female Vocalist in both 1970 (as a member of her one- or two-off band Fotheringay) and 1971 (when she was promoting her first solo album, The North Star Grassman and the Ravens). Although it's not mentioned in the Fairport rendition, most versions of "Tam Lin" explain that Janet was the heir to Carterhaugh Woods. When the fairies--or Tam Lin as their emissary--forbid her to enter the woods that in fact belong to her, they're not necessarily fighting words, but only because mortals had traditionally not dared to defy the powerful fey in the matter.

Although it's not mentioned in the Fairport rendition, most versions of "Tam Lin" explain that Janet was the heir to Carterhaugh Woods. When the fairies--or Tam Lin as their emissary--forbid her to enter the woods that in fact belong to her, they're not necessarily fighting words, but only because mortals had traditionally not dared to defy the powerful fey in the matter.  Sandy Denny's voice at her height, on "Tam Lin," young and powerful, five, six, seven years before things would dissipate messily, is like furniture of fine burnished wood. You can almost smell the lemon oil, watch the rag infused with its essence as it slides frictionless across that polished table top.

Sandy Denny's voice at her height, on "Tam Lin," young and powerful, five, six, seven years before things would dissipate messily, is like furniture of fine burnished wood. You can almost smell the lemon oil, watch the rag infused with its essence as it slides frictionless across that polished table top.

So, y'know, in this oh-so-artistic way that he has, Tarantino is not as annoying as his ultraviolent grandfather Scorsese, but, to be sure, the end result is the same. I wind up thinking of guys in pinstripe suits hanging on meathooks inside of refrigerated trucks when I hear "Layla," and I think of Mr. Blonde when I hear a certain Scottish folk rock band performing their biggest hit.

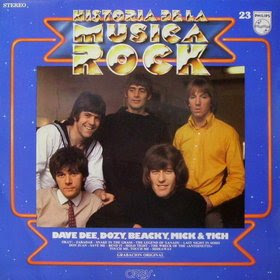

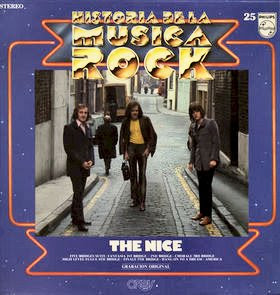

So, y'know, in this oh-so-artistic way that he has, Tarantino is not as annoying as his ultraviolent grandfather Scorsese, but, to be sure, the end result is the same. I wind up thinking of guys in pinstripe suits hanging on meathooks inside of refrigerated trucks when I hear "Layla," and I think of Mr. Blonde when I hear a certain Scottish folk rock band performing their biggest hit.  In addition to other rock and roll books, including biographies of The Who, Pink Floyd and Rick Wakeman (!), Sierra i Fabra had some ten years earlier also written a reference work called La Historia de la Musica Pop, so we can assume a name for the new project came fairly easily for them.

In addition to other rock and roll books, including biographies of The Who, Pink Floyd and Rick Wakeman (!), Sierra i Fabra had some ten years earlier also written a reference work called La Historia de la Musica Pop, so we can assume a name for the new project came fairly easily for them. Of course, Lillian Roxon's English language Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock had outlived its original editor and gone into its second or third edition by this time, so Prado's large encyclopedia might have remained of limited interest to an Anglo like myself . . .

Of course, Lillian Roxon's English language Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock had outlived its original editor and gone into its second or third edition by this time, so Prado's large encyclopedia might have remained of limited interest to an Anglo like myself . . .

And for some reason they gave Roger Daltrey a record after having already given one to The Who? What was it, the McVicar soundtrack?

And for some reason they gave Roger Daltrey a record after having already given one to The Who? What was it, the McVicar soundtrack?